Foreword

We had in mind a study of the practical aspects of the relations between psychiatry and criminal justice. In the course of our research we came across Pierre Riviere’s case.It was reported in the Annales d’hygiène publique et de médecine légale in 1836. Like all other reports published in that journal, this comprised a summary of the facts and the medico-legal experts’ reports. There were, however, a number of unusual features about it.A series of three medical reports which did not reach similar conclusions and did not use exactly the same kind of analysis, each coming from a different source and each with a different status within the medical institution: a report by a country general practitioner, a report by an urban physician in charge of a large asylum, and a report signed by the leading figures in contemporary psychiatry and forensic medicine (Esquirol, Marc, Orfila, etc.). A fairly large collection of court exhibits including statements by witnesses – all of them from a small village in Normandy – when questioned about the life, behavior, character, madness or idiocy of the author of the crime. Lastly, and most notably, a memoir, or rather the fragment of a memoir, written by the accused himself, a peasant some twenty years of age who claimed that he could “only barely read and write” and who had undertaken during his detention on remand to give “particulars and an explanation” of his crime, the premeditated murder of his mother, his sister, and his brother. A collection of this sort seemed to us unique among the contemporary printed documentation.

[…]

To be frank, however, it was not this, perhaps, that led us to spend more than a year on these documents. It was simply the beauty of Riviere’s memoir. The utter astonishment it produced in us was the starting point.

Foucault’s full foreword available here:

https://foucault.info/documents/foucault.pierreRiviere.foreword/

Excerpt from the Memoir:

Particulars and explanation

of the occurrence

on June 3 in Aunay at the village of la Faucterie

written by the author of this deed

I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother, and wishing to make known the motives which led me to this deed, have written down the whole of the life which my father and my mother led together since their marriage. I was witness of the greater part of the facts, and they are written at the end of this history; as regards the beginning I heard it recounted by my father when he talked of it with his friends and with his mother, with me, and with those who had knowledge of it. I shall then tell how I resolved to commit this crime, what my thoughts were at the time, and what was my intention. I shall also say what went on in my mind after doing this deed, the life I led among people, and the places I was in after the crime up to my arrest and what were the resolutions I took. All this work will be very crudely styled, for l know only how to read and write; but all I ask is that what I mean shall be understood, and I have written it all down as best as I can.

Summary of the tribulations and afflictions

which my father suffered at the

hands of my mother

from 1813 to 1835

My father was the second of the three sons of Jean Riviere and Marianne Cordel, he was brought up in honesty and religion, he was always of a mild and peaceable disposition and affable toward all, and so was esteemed by all who knew him.

[…]

In the marriage contract it was stipulated thar my mother had some good pieces of furniture. But it is only a matter of course that people put that in contracts; she had none, and since she needed a bed and there was one for sale in a village not far away, she told my father she wanted it. He asked her whether she would not rather have a new one, but she said no, and kept at him telling him that he should be too late getting there. My father then thought he would buy it no matter what the price, and he bought it for about what it was worth, but during the sale other women told my mother that they would nor want secondhand rubbish, and she told my father that she did not want it and it was too dear; he answered her: but it is bought now, someone must use it. She said she did not want it, my father said: it is not worth so much fuss and took the bed away and had to resell it. At the beginning of 1815 my mother gave birth to me, and the birth made her very ill. My father took all proper care of her, he did not go to bed for six weeks, he said at the time he would go to bed later, he could not sleep, he was accustomed to lie awake. ln this illness of my mother’s her breasts went bad and my father sucked them to extract the poison, and then spat it out on the ground. During her illness my mother displayed contempt and harshness especially toward her mother, she maintained that she was not capable of doing anything for her; she then maintained that my paternal grandmother was the only one who was able to look after her. When she asked her why she did not want it to be her mother, she answered: oh because she is so stupid.

[…]

Noon came and [my grandmother] went off to milk the cows with my sister Aimee. My brother Jule had come back from school. Taking advantage of this opportunity I seized the bill, I went into my mother’s house and I committed that fearful crime, beginning with my mother, then my sister and my little brother, after that I struck them again and again; Marie, Nacivel’s mother-in-law came in, ah what are you doing, she said to me, go away, I said to her, or I shall do as much to you. Then I went our into the yard and speaking to Nativel I said: Miché go and make sure that my g-m does not do herself any harm, she can be happy now, I die to restore her peace and quiet, I also spoke to Aimee Lerot and to Patel, Lerot’s servant, see to it, I said, that my father and my g-m do not do themselves a mischief, I die to restore them peace and quiet. Then I set off to go to Vire; as I wished to have the glory of being the first to announce this news there I did not want to go to the town of Aunay, for fear I might be arrested there. I resolved to go by the woods of Aunay by a road on which I had been several times which passes near a place called les Vergées, and to reach the road to Vire above the village at the foot of the wood of Aunay; I therefore took that road and I threw away my bill into a wheatfield near la F aucterie and went off. As I went I felt this courage and this idea of glory that inspired me weaken, and when I had gone farther and came into the woods I regained my full senses, ah, can it be so, I asked myself, monster that I am! Hapless victims! can I possibly have done that, no it is but a dream! ah but it is all too true! chasms gape beneath my feet, earth swallow me; I wept, I fell to the ground, I lay there, I gazed at the scene, the woods, I had been there before. Alas, I said to myself, little did I think I would one day be in this plight; poor mother, poor sister, guilty maybe in some sort, but never did they have ideas so unworthy as mine, poor unhappy child, who came plowing with me, who led the horse, who already harrowed all by himself, they are annihilated forever these hapless ones. Nevermore will they be seen on earth! Ah heaven, why have you granted me existence, why do you preserve me any longer. I did not stay long in that place, I could not stay at this spot, my regrets faded somewhat as I walked on.

[…]

I walked all saturday. I kept thinking they would arrest me, meanwhile as I had hardly any more money, I resorted to make a bow to kill birds and feed on them, or to amuse myself trying to kill some, and if they should arrest me with it, it might rather serve than harm the role l would be playing; but since I would have to cook any I could kill, as I passed through Halcour I bought a watch glass which cost me 4 sous to light a fire by the sun, thinking it would have the same effect as spectacles, but having tried it and seeing that it was no use I broke it. I had taken the road from Halcour to Caen, I came to a town, I went into a shop, I bought two sou’s worth of tinder, a sou’s worth of sulphur, I had flints which I had gathered on the road and with my knife I could strike a spark, I had some pages from a breviary and an almanac, which I happened to have on me when I left, I could use them for matches. I also bought a sou’s worth of walnuts, I went into a baker’s and bought two pounds of griddle-cake, in the afternoon I rested in the meadows by the hedges, and I caught a young lark. I put the bird in my pocket and went on my way, I had only four sous left, I spent them that evening on a quart of cider and a small butter griddle-cake, and I spent the night in a wheatfield; in the morning I passed through Caen, I took the road to Falaise and went into the woods near Langannerie, I gathered some sticks of dry wood, I lighted a fire at the foot of a tree which preventcd the wind from putting it out, and I roasted the lark; it will perhaps be said that I also caught chickens and ducks and other things and took faggots from woodpiles; but the remains can still be found in the wood where I lit my fire and a few sticks piled up, or if they are no longer there consult those who removed them, all that is to be found is I say only a few dry sticks gathered in the wood and only the feathers from the lark. I came therefore to these woods on Sunday; after eating the lark, I made a bow and several arrows. I had found a long nail on the road; by dint of filing it with the less good of my knives I managed to break its head off, and I put it on the end of one of the arrows (the other arrows are still there if they have not been removed they are in the tree near which I made the fire) then I used this weapon to try and kill birds, but I could not manage this; if I had found any frogs too, I would have cut off their legs and roasted them, but I did not find any. I spent four days in these woods, they are three small woods not very far from each other, in one of which many strawberries grow, I ate them, and I thought to myself, either I shall be arrested, or I shall live in this way, or I shall die. Seeing some more woods, further along the road, I resolved to go and see if there was anything to eat in them until other fruits were ripe in the woods where I was; and I thought that until they arrested me, I would come and go from one wood to another to get my food. So I left on the Thursday morning, and I came to the town of Langannerie with my bow under my arm, as I was passing someone said: oh look, there is a fellow carrying a bow. I had soon passed through the town and was at the last houses, when a gendarme who was not in uniform, passing near me, surveyed me, and asked me: where are you from my friend? I replied in accordance with my system, I am from everywhere. –Have you any papers –No –What are you doing here –God is conducting me, and I adore him –Ho, I believe I have some business with you, where are you from –I started from Aunay –What is your name –Rivière –Ah yes come with me I have something to say to you –What do you want of me –Come on come on I will tell you. And then speaking to a woman who was I think from his household, oh, he said, it is the fellow from Aunay. He took me into a room searched me and took charge of everything I had. When he was about to put me in the cells, are you, he asked, the fellow who killed your mother? Yes, I answered him, God inspired me, he ordered me to do it, I obeyed his orders, and he is protecting me. Ah yes so that is it, he said, opening the door of the cell, go on my lad, get in there. I afterwards maintained this method of defense ac Falaise and at Conde, it was very painful for me to maintain such things and to say that I did not repent; when I came to Vire I thought I would declare the truth, but when I appeared before the Prosecutor Royal, I maintained the same thing. When they had left me by myself, I rcsolved afresh to tell the truth, and I confessed to the jailer who came and talked to me, and I told him that I intended to declare everything before my judges; but when I went to my first interrogation before the examining judge, I could not yet make up my mind to it and I maintaincd the system of which I have spoken until the jailer told what I had said to him. I was very glad at his statement, it relieved me of a great weight which was crushing me. Then without disguising anything, I declared everything which had brought me to this crime. They told me to put all these things down in writing, I have written them down; now that I have made known all my monstrosity, and that all the explanations of my crime are done, I await the fate which is destined for me, I know the article of the penal code concerning parricide, I accept it in expiation of my faults, alas if only I could see the hapless victims of my cruelty alive once more, even if for that I must suffer the utmost torments; but no it is vain, I can only follow them, so I therefore await the penalty I deserve, and the day which shall put an end to all my resentments.

THE END

This manuscript begun on July 10, 1835 in the jail at Vire, and finished at the same place on the 21st of the same month.

Pierre Rivière

Excerpts from:

I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother… Ed. Michel Foucault, trans. Frank Jellinek, Random House, New York 1975

Orig. French edition:

Moi, Pierre Rivière, ayant égorgé ma mère, ma soeur et mon frère… Ed. Michel Foucault et al, Éditions Gallimard/Juilliard, Paris 1973

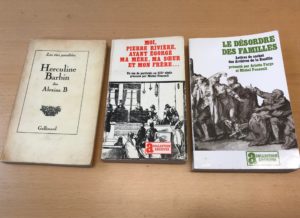

Between 1973 and 1982, Foucault edited three books consisting of found texts: I, Pierre Rivière, a 19th century memoir in which a young man explains how and why he killed his mother and some of his siblings, Herculine Barbin, the autobiographical account of a 19th century hermaphrodite or what is today known as intersex person, and in cooperation with historian Arlette Farge, the Disorderly Families, a collection of ”letters of arrest” sent by common people to the king or police lieutenant in 18th century Paris, in which they requested the incarceration of immoral, dangerous, or unruly family members. Here, Found Review looks closer at some aspects of these found works.