Introduction

(by Arlette Farge and Michel Foucault)

The idea that history is dedicated to “archival exactitude” and philosophy to the “architecture of ideas” is, to us, nothing short of preposterous. This is not how we work.

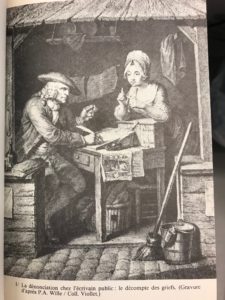

One of us studied Parisian street life in the eighteenth century; the other, the procedures for administrative imprisonment from the seventeenth century up to the Revolution. Both of us came to work with what are called the “Archives of the Bastille,” which are stored in the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal. These are, for the most part, dossiers concerning police matters that were compiled at the Bastille, scattered by the Revolution and later reassembled.

Reading through these archives, the two of us had been struck by certain facts. First, there was the large number of these dossiers that pertained to lettres de cachet and, more precisely, requests addressed either to the lieutenant of police or directly to the Maison du Roi that sought to obtain from the sovereign an “order” that would restrict an individual’s freedom (sometimes through house arrest or exile, but more often than not through imprisonment). We were also struck by the fact that, in many cases, these requests dealt with family matters that were altogether private: minor conflicts between parents and children, marital disagreements, the misbehavior of a spouse, the disorder of a boy or girl. It also became clear to us that the large majority of these requests came from modest, sometimes even quite poor, households—from the small-time vendor or artisan to the market gardener, the secondhand clothes seller, the domestic servant, or the day laborer. Finally, we noticed that, despite the fragmentary nature of these archives, we could often find a whole series of related documents surrounding these requests for imprisonment: statements from neighbors, families, or entourages, the investigation of the police superintendent, the king’s decision, requests for release coming from the victims of imprisonment or even from those who had initially requested it.

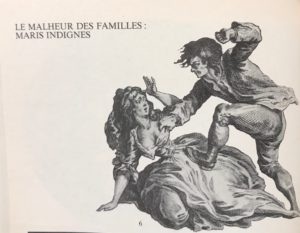

For all of these reasons, it seemed to us that these documents could offer a fascinating peek into the landscape of daily life for the lower classes in Paris during the era of the absolute monarchy—or at the very least for a certain period of the Ancien Régime. One might think that these lettres de cachet would offer documentation of royal absolutism, of the manner in which the monarch punished his enemies or helped an important family get rid of one of its members. Yet it was not royal anger that we found while combing through these dossiers, but rather the passions of the common people, at the center of which were family relationships—husbands and wives, parents and children.

After a few words about the history of lettres de cachet, the way in which they functioned, and the reasons that guided our choices amid this mass of documents, we will provide the unabridged dossiers that we have selected: namely, those that concerned requests by a husband or wife for the imprisonment of a spouse or by parents for the imprisonment of their children, for the years 1728 and 1758. In a final chapter, we will indicate several perspectives that we believe emerge from this grouping of documents. […]

(From section Marital Discord, Households in ruin)

Geneviève Le Maître

Christophe Aymond journeyman carpenter residing rue Poissonnière in the lodging of Monsieur de Vitry, master ribbon maker, most humbly represents unto Your Highness that Geneviève Le Maître his wife of twelve years has thrice ruined him and destroyed his household through her unruly conduct and currently is no longer with the supplicant so as to have more liberty to live in debauchery, she is continually drunken and prostitutes herself publicly to the first passerby, she frequents only people of her ilk, with whom she eats up and dissipates everything that she can grab, such that in order to avoid the misfortune of which she is capable through her conduct which is unruly and given to all manner of vices, her own mother the widow Le Maître, and her family have joined the supplicant, to most humbly beseech Your Highness to have the charity to grant an order to have said Geneviève Le Maître locked up in the hospital. They will never cease their prayers for the preservation of Your Highness.

[On the back of the above petition]

January 31, 1728.

I have written to one Le Maître, the wife of Aymond, against whom this petition was presented to you, but she has not seen fit to come speak with me. All those who signed and certified this petition who are the mother, father-in- law and others in the family came to see me and assured me of the bad conduct [mauvaise conduite] of said Aymond wife and of her prostitution and constant drunkenness that she is at present a vagabond, without lodging, and it was only by happenstance that Monsieur Josse, officer of the short robe [robe courte], who was willing to carry the billet I had written her telling her to come speak with me knew where she retired at night. I therefore believe that there is reason to have her locked up in the hospital for correction.

The Superintendent Aubert.

Ars. Arch. Bastille 10998, fol. 231 (1728)

(From section Marital Discord, The Debauchery of Husbands)

Pierre Blot

To My Lord the Lieutenant General of Police My Lord, Marianne Perrin, wife of Pierre Blot, residing rue de la Cordonnerie, in the residence of M. Le Tellier, wine merchant, Saint-Eustache parish, most humbly represents unto Your Highness that for the last six years said Blot has been feeble-minded, he was treated for three months at the Hôtel-Dieu, but instead of recovering, his wits became more disturbed such that he tried to kill the supplicant his wife and a daughter of around two months that the supplicant is nursing, and he abuses a daughter age eight and a half. In short, their lives are in no way safe. As all the neighborhood can confirm and attest to the truth, the supplicant appeals to Your Highness, that it would please you to give an order that said Pierre Blot be arrested and taken to the château de Bicêtre to the madhouse [salle des fous] as she fears the further ills that could only come of this, and she will never cease to continue her wishes for the preservation of the health of My Lord. Tellier (primary leaseholder), Gervais.

[On the same petition]

Monsieur, I have the honor of reporting to you that the complaints made by the wife of Pierre Blot against her husband are just, she has every reason to fear her husband’s madness. It would be a charity to place him in Bicêtre; several attempts have been made to cure him but it appears to me that his ill [mal] is incurable, the present can be sent to Monsieur the Superintendent Machurin.

Pouffis, this March 12, 1758.

Ars. Arch. Bastille 11988, fol. 60 (1758)

To My Lord the Lieutenant General of Police My Lord,

Marianne Perrin, wife of Pierre Blot, porter in the flour market in la Halle, residing rue de la Cordonnnerie, Saint-Eustache parish, most humbly represents unto Your Highness that her husband is detained in the common prisoner’s room [salle de force] of Bicêtre for being of slightly alienated wits, but that he never insulted anyone, nor committed any base deeds, it was only the supplicant along with her two children who suffered a little, he always offered his services to the public in the said Halles with honor and probity and as he has put himself in God’s hands his spirit is completely calm as it would appear from the certificate of his confessor enclosed herein. This obliges the supplicant to appeal unto Your Highness, that it might please you, My Lord, to release said Pierre Blot her husband, so that he could return home to work as before and earn a living for his children, she dares to hope for this grace from Your ordinary Justice and she will never cease to pray God for the preservation and health of Your Highness.

C. Gervais, M. Vanogenne, Griffault (baker), Gioibisce.

I the undersigned, sacristan priest of the church of Bicêtre, certify to whom it may concern that I heard the confession of Pierre Blot, prisoner in the common prisoner’s room of the Bicêtre. This present certificate was given this July 18, 1758.

Guiard, priest.

(From section Parents and Children, The Dishonor of Waywardness)

Edme Joseph Eli

To My Lord Bertin, Lieutenant General of Police My Lord, Joseph Eli, traveling wine merchant and his wife, residing place Maubert, most humbly remonstrate unto Your Highness that they have the misfortune of having for a son Edme Joseph Eli, age nineteen, for whose upbringing they spared no expense and after having employed every kind approach to recall him to his duty, they were unable to gain any change in his conduct, they have the sorrow of seeing that their son instead of behaving in an orderly manner passes his days in debauchery, frequenting a number of libertines with whom he libertines and debauches himself and spends his nights who knows where without the supplicants being able to learn where he sleeps, which has made the supplicants fear for the worst. This is what obliges them to appeal unto the authority of Your Highness to beseech him to order that he be locked up in Bicêtre where he was already locked up last year as a punishment for his unruliness and to prevent him from dishonoring his family, and for this they wish to Heaven for the prosperity of Your Highness.

Eli (father).

This declaration is truthful, the father and the mother, my parishioners are honest folk; they deserve the kindness of Monsieur the Lieutenant General of Police.

Pregnault, curé of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont.

The petition is signed by Villy, Md Chapellier, Saint-Étienne-du-Mont parish, Philippe Thomas Morel, lawyer (knows the Eli son to be a vagabond), Megret, primary leaseholder.

Ars. Arch. Bastille 12000, fol. 36 (1758) May 15, 1756.

Monsieur Chaban

Monsieur,

Enclosed is the petition that one Eli presented unto you to have his son locked up in Bicêtre. I postponed reporting unto you the clarifications that I made regarding the conduct of this young man for some time because the father and the mother having decided he would work for the masons, engaged me to wait until they had been assured of the changes that they hoped to see in him. But now they complain once again that their son continues to be disturbed, that he has completely abandoned their house where he no longer returns to sleep, that he sleeps in the market stalls of place Maubert to spend the night with other vagabonds like himself and that he has no occupation.

These facts as well as those in the memoir were attested to me by different persons who have spoken with a single voice about it. I therefore esteem, Monsieur, that there is no hindrance to granting the requested order. I am with a profound respect Monsieur your most humble servant.

Superintendent Lemaire.

Ars. Arch. Bastille 12000, no folio (1758)

Arlette Farge & Michel Foucault

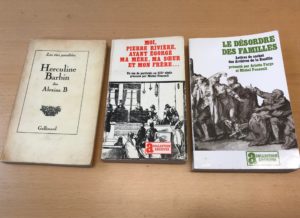

Disorderly Families: Infamous letters from the Bastille Archives

Transl. Thomas Scott-Railton

University of Minnesota Press, 2016

Between 1973 and 1982, Foucault edited three books consisting of found texts: I, Pierre Rivière, a 19th century memoir in which a young man explains how and why he killed his mother and some of his siblings, Herculine Barbin, the autobiographical account of a 19th century hermaphrodite or what is today known as intersex person, and in cooperation with historian Arlette Farge, the Disorderly Families, a collection of ”letters of arrest” sent by common people to the king or police lieutenant in 18th century Paris, in which they requested the incarceration of immoral, dangerous, or unruly family members. Here, Found Review looks closer at some aspects of these found works.