Excerpt (pp. 119-123) from Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, 1990/1999:

Foucault, Herculine, and the Politics

of Sexual Discontinuity

Foucault’s genealogical critique has provided a way to criticize those Lacanian and neo-Lacanian theories that cast culturally marginal forms of sexuality as culturally unintelligible.Writing within the terms of a disillusionment with the notion of a liberatory Eros, Foucault understands sexuality as saturated with power and offers a critical view of theories that lay claim to a sexuality before or after the law.When we consider, however, those textual occasions on which Foucault criticizes the categories of sex and the power regime of sexuality, it is clear that his own theory maintains an unacknowledged emancipatory ideal that proves increasingly difficult to maintain, even within the strictures of his own critical apparatus.

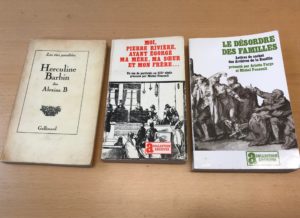

Foucault’s theory of sexuality offered in The History of Sexuality, Volume I is in some ways contradicted by his short but significant introduction to the journals he published of Herculine Barbin, a nineteenthcentury French hermaphrodite. Herculine was assigned the sex of “female” at birth. In h/er early twenties, after a series of confessions to doctors and priests, s/he was legally compelled to change h/er sex to “male.” The journals that Foucault claims to have found are published in this collection, along with the medical and legal documents that discuss the basis on which the designation of h/er “true” sex was decided. A satiric short story by the German writer, Oscar Panizza, is also included. Foucault supplies an introduction to the English translation of the text in which he questions whether the notion of a true sex is necessary. At first, this question appears to be continuous with the critical genealogy of the category of “sex” he offers toward the conclusion of the first volume of The History of Sexuality. However, the journals and their introduction offer an occasion to consider Foucault’s reading of Herculine against his theory of sexuality in The History of Sexuality,Volume I. Although he argues in The History of Sexuality that sexuality is coextensive with power, he fails to recognize the concrete relations of power that both construct and condemn Herculine’s sexuality. Indeed, he appears to romanticize h/er world of pleasures as the “happy limbo of a non-identity” (xiii), a world that exceeds the categories of sex and of identity.The reemergence of a discourse on sexual difference and the categories of sex within Herculine’s own autobiographical writings will lead to an alternative reading of Herculine against Foucault’s romanticized appropriation and refusal of her text.

In the first volume of The History of Sexuality, Foucault argues that the univocal construct of “sex” (one is one’s sex and, therefore, not the other) is (a) produced in the service of the social regulation and control of sexuality and (b) conceals and artificially unifies a variety of disparate and unrelated sexual functions and then (c) postures within discourse as a cause, an interior essence which both produces and renders intelligible all manner of sensation, pleasure, and desire as sexspecific. In other words, bodily pleasures are not merely causally reducible to this ostensibly sex-specific essence, but they become readily interpretable as manifestations or signs of this “sex.”

In opposition to this false construction of “sex” as both univocal and causal, Foucault engages a reverse-discourse which treats “sex” as an effect rather than an origin. In the place of “sex” as the original and continuous cause and signification of bodily pleasures, he proposes “sexuality” as an open and complex historical system of discourse and power that produces the misnomer of “sex” as part of a strategy to conceal and, hence, to perpetuate power-relations. One way in which power is both perpetuated and concealed is through the establishment of an external or arbitrary relation between power, conceived as repression or domination, and sex, conceived as a brave but thwarted energy waiting for release or authentic self-expression. The use of this juridical model presumes that the relation between power and sexuality is not only ontologically distinct, but that power always and only works to subdue or liberate a sex which is fundamentally intact, selfsufficient, and other than power itself. When “sex” is essentialized in this way, it becomes ontologically immunized from power relations and from its own historicity. As a result, the analysis of sexuality is collapsed into the analysis of “sex,” and any inquiry into the historical production of the category of “sex” itself is precluded by this inverted and falsifying causality. According to Foucault, “sex” must not only be recontextualized within the terms of sexuality, but juridical power must be reconceived as a construction produced by a generative power which, in turn, conceals the mechanism of its own productivity:

“the notion of sex brought about a fundamental reversal; it made it possible to invert the representation of the relationships of power to sexuality, causing the latter to appear, not in its essential and positive relation to power, but as being rooted in a specific and irreducible urgency which power tries as best it can to dominate.” (154)

Foucault explicitly takes a stand against emancipatory or liberationist models of sexuality in The History of Sexuality because they subscribe to a juridical model that does not acknowledge the historical production of “sex” as a category, that is, as a mystifying “effect” of power relations. His ostensible problem with feminism seems also to emerge here: Where feminist analysis takes the category of sex and, thus, according to him, the binary restriction on gender, as its point of departure, Foucault understands his own project to be an inquiry into how the category of “sex” and sexual difference are constructed within discourse as necessary features of bodily identity. The juridical model of law which structures the feminist emancipatory model presumes, in his view, that the subject of emancipation, “the sexed body” in some sense, is not itself in need of a critical deconstruction. As Foucault remarks about some humanist efforts at prison reform, the criminal subject who gets emancipated may be even more deeply shackled than the humanist originally thought. To be sexed, for Foucault, is to be subjected to a set of social regulations, to have the law that directs those regulations reside both as the formative principle of one’s sex, gender, pleasures, and desires and as the hermeneutic principle of selfinterpretation. The category of sex is thus inevitably regulative, and any analysis which makes that category presuppositional uncritically extends and further legitimates that regulative strategy as a power/ knowledge regime.

In editing and publishing the journals of Herculine Barbin, Foucault is clearly trying to show how an hermaphroditic or intersexed body implicitly exposes and refutes the regulative strategies of sexual categorization. Because he thinks that “sex” unifies bodily functions and meanings that have no necessary relationship with one another, he predicts that the disappearance of “sex” results in a happy dispersal of these various functions, meanings, organs, somatic and physiological processes as well as in the proliferation of pleasures outside of the framework of intelligibility enforced by univocal sexes within a binary relation.The sexual world in which Herculine resides, according to Foucault, is one in which bodily pleasures do not immediately signify “sex” as their primary cause and ultimate meaning; it is a world, he claims, in which “grins hung about without the cat” (xiii). Indeed, these are pleasures that clearly transcend the regulation imposed upon them, and here we see Foucault’s sentimental indulgence in the very emancipatory discourse his analysis in The History of Sexuality was meant to displace. According to this Foucaultian model of emancipatory sexual politics, the overthrow of “sex” results in the release of a primary sexual multiplicity, a notion not so far afield from the psychoanalytic postulation of primary polymorphousness or Marcuse’s notion of an original and creative bisexual Eros subsequently repressed by an instrumentalist culture.

[….]

Full text here: judith-butler-gender-trouble-feminism-and-the-subversion-of-identity-second-edition

Judith Butler

Gender Trouble

Routledge, New York & London 1990/1999